?? Also see Debbie’s Main FAQ index: Frequently Asked Questions

This is a question I often get asked, so I thought I’d finally write a post about it. Also do check out this excellent post by Naseem Hrab that includes answers from various Canadian publishers.

In all the books I’ve ever illustrated (picture books and chapter books) but not written, I have never worked directly with the author during the creative process. Before I became a children’s book illustrator, I had always assumed that the author and illustrator would work closely together throughout – aren’t they a TEAM, after all?

What I was shocked to discover, when I was asked to illustrate my first picture book by Simon & Schuster: that the illustrator is given a LOT of creative freedom. I was used to being micromanaged by freelance art clients when I used to do custom illustrations, being told exactly what I was supposed to draw. When I was told that Michael Ian Black (author), Laurent Linn (S&S art director) and Justin Chanda (S&S editor/publisher) wanted to see what MY vision was, I was both terrified and excited.

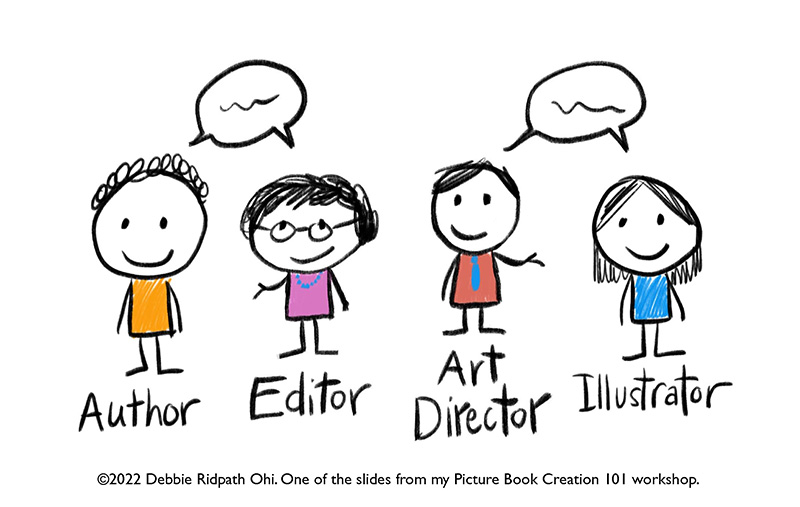

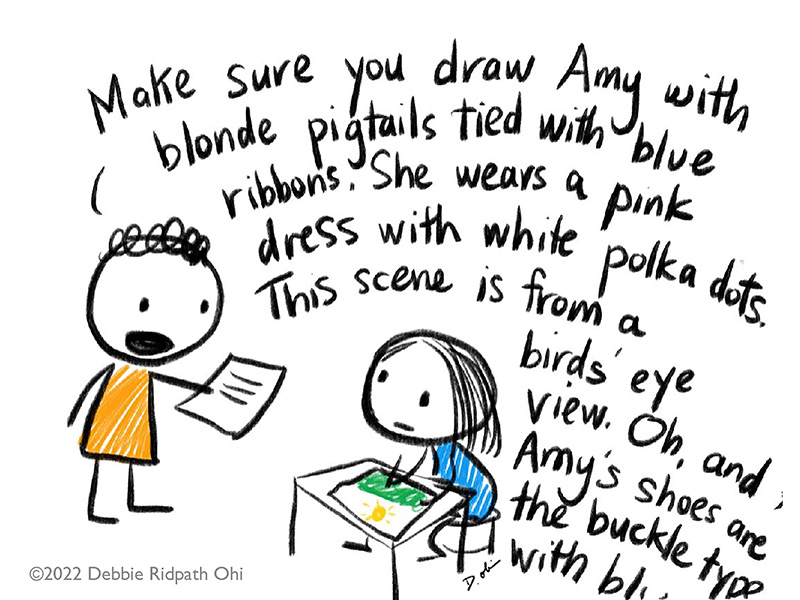

One of my early mentors (Cecilia Yung, art director at Penguin) explained that keeping the author and illustrator separate during the creative process is to protect the illustrator. She said that authors tend to already be very opinionated and feel strongly about their own vision for their story and if they were allowed to interact closely with the illustrator throughout, there would be a lot of “draw this, no not like, like THIS”:

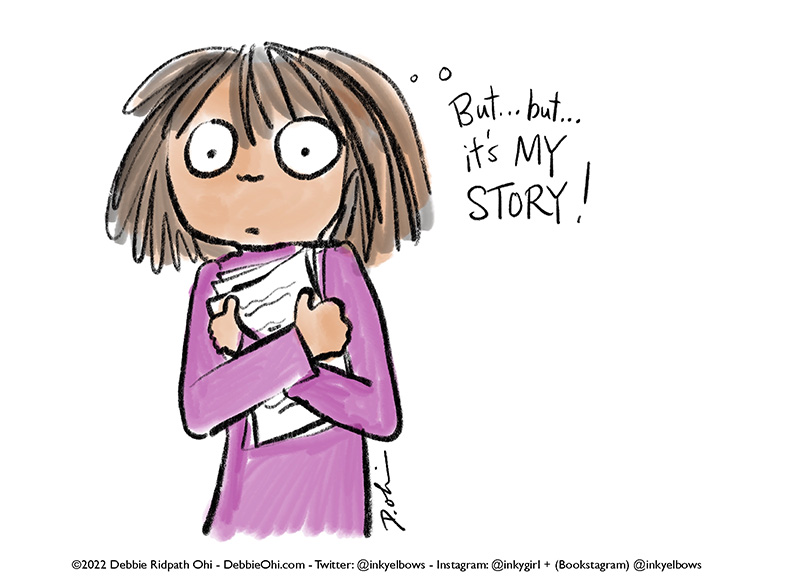

Many authors also don’t appreciate how much the illustrator’s own vision can enhance the book.

Authors may also be shocked to find out that sometimes they may even be asked to CHANGE THE TEXT because of the illustration process.

This has happened several times during my books with Michael Ian Black. I feel INCREDIBLY lucky that Michael is an author who trusts the illustrator completely.

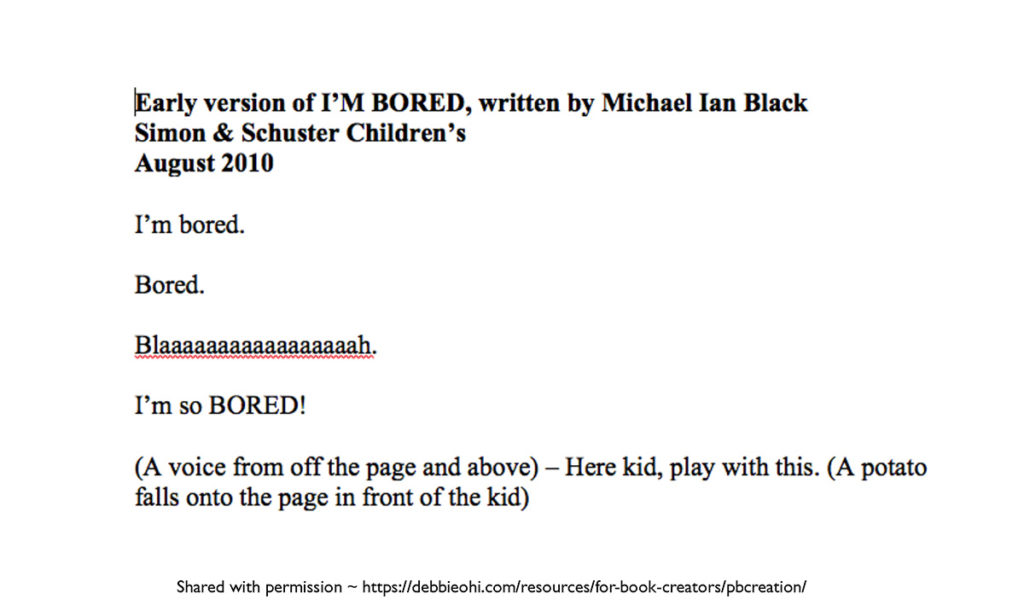

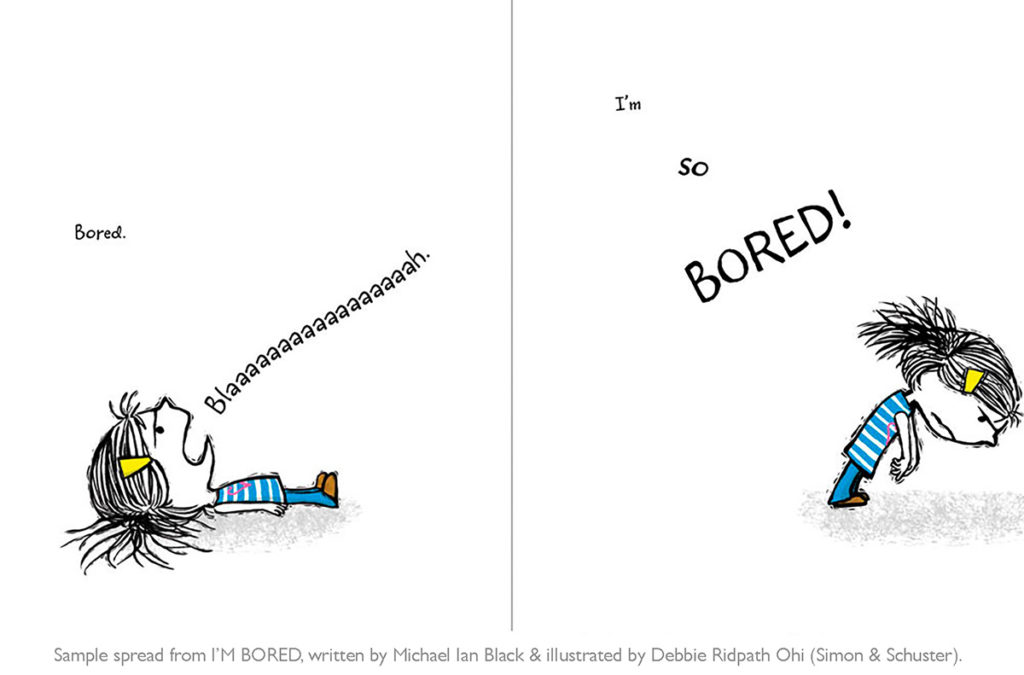

The very first picture book I was asked to illustrate was I’M BORED, written by Michael. Here’s the first version of the manuscript that Justin Chanda (our editor) sent me:

Notice the lack of page breaks. Notice that Michael didn’t even specify the gender of the child (!). This was all left up to me.

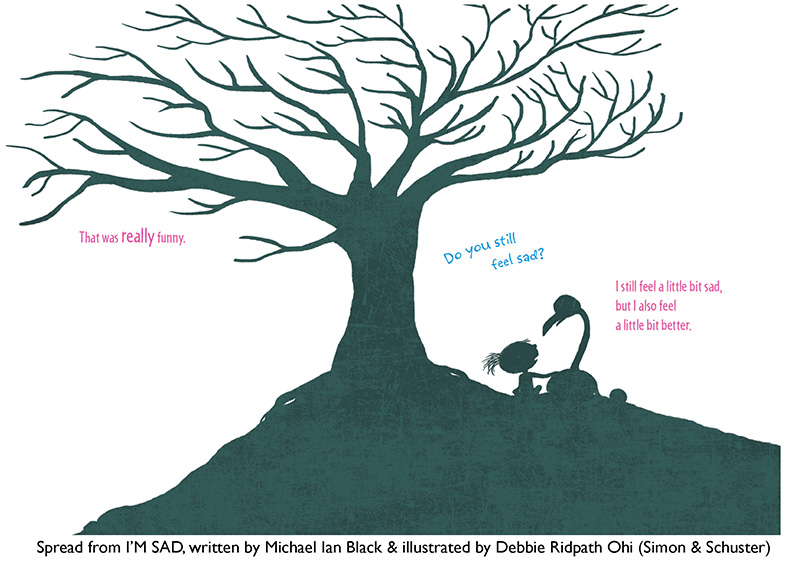

And in an example that shows how the ending of a book changed because of my illustrations, take I’M SAD. The ending was originally supposed to be funny, with the Potato trying to follow an astronaut out into space. I love Michael’s quirky sense of humour!

I went through a couple of rounds of sketches, but the art director and editor really liked one of the illustrations I came up for a bittersweet moment before the end. The editor talked to Michael about the possibility of changing the ending, and Michael was totally on board. (YES, I continue to feel very lucky to be working with this creative team for so many reasons).

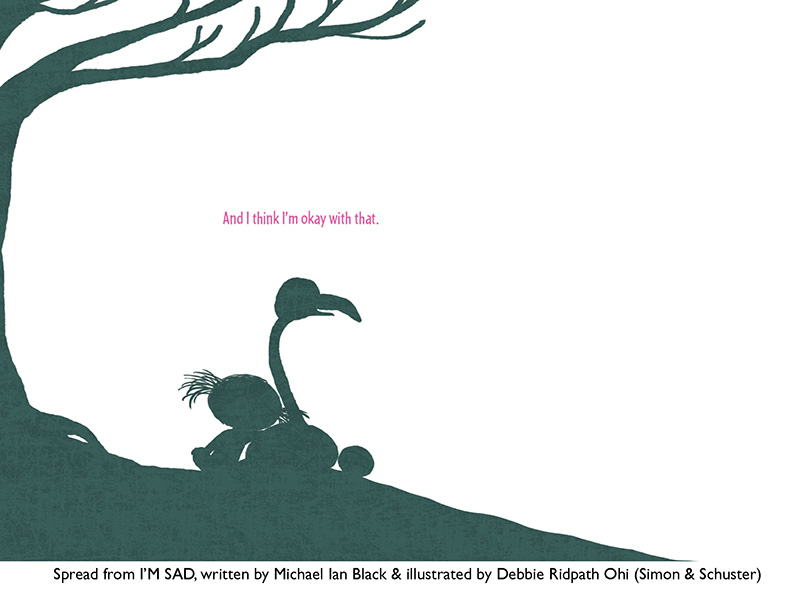

Here’s the new ending to I’M SAD:

None of this would have happened if the author, editor and art director hadn’t given me the freedom to bring my own vision to the project. A side note about I’M SAD – when I first read Michael’s mss, I cried. Part of it was because of what was going on in my life at the time but also because Michael is such such an amazing writer. But the problem was that I cried pretty much every time I started working on it, so I read the mss over and over again until it DIDN’T make me cry anymore, so I could be more objective and do a better job as an illustrator.

NOTE: Although most traditional publishing houses tend to keep the author and illustrator separate during the creative process (including houses I’ve worked with: Simon & Schuster, Random House, HarperCollins), there are always exceptions. Sometimes the author and illustrator have approached the publishing house as a team, for example, or have already worked closely together. Or the nature of a book requires more interaction between the author and illustrator, especially for nonfiction, or when different cultures are involved. I’ve heard from some of my illustrator friends that certain publishers DO closely involve the author throughout the creative process.

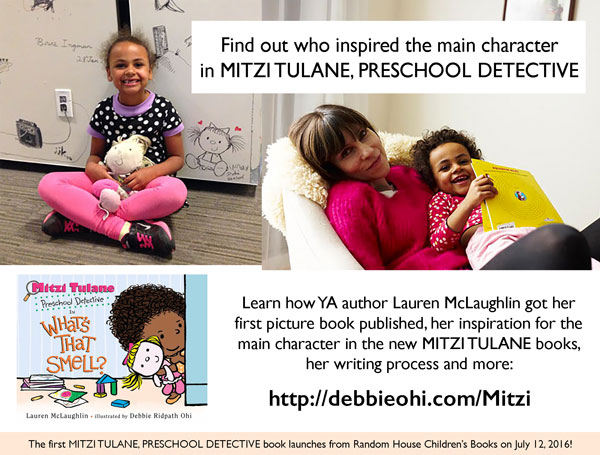

When I was asked to illustrate the Mitzi Tulane picture books, the editor forwarded a request from the author, asking if the main character’s doll could look like her own daughter’s doll. I said yes, of course, because the main character was based on Lauren McLaughlin’s adopted daughter and so was the doll, Gigi Gaboo.

You can find out more about how Mitzi Tulane was made here.

Anyway, I could go on WAY too long on this topic (and have, during workshops I’ve given on the picture book creative process), but here are some additional resources you might find useful:

My other FAQ entry: “I just finished writing my picture book story. What next? How do I find an illustrator?”

Why Do We Keep Picture Book Authors and Illustrators Apart? or How To Play Well With Others – by Naseem Hrab

SCBWI Frequently Asked Questions

Thanks for this. It was very helpful!