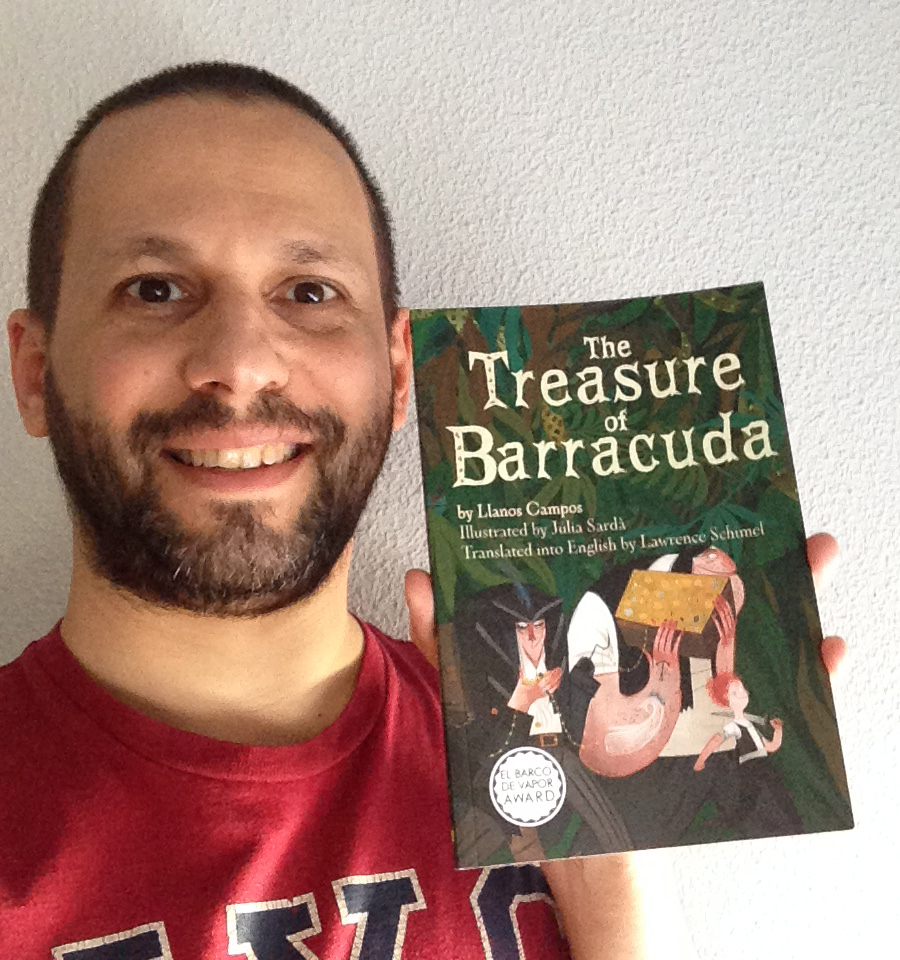

I’ve been grateful to Lawrence Schimel for his support and encouragement early in my career. We met online years before we finally met in person in NYC:

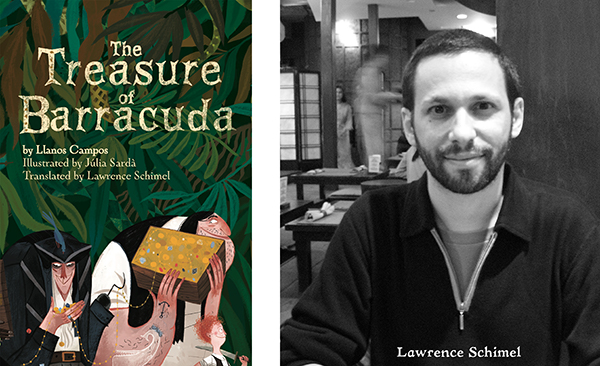

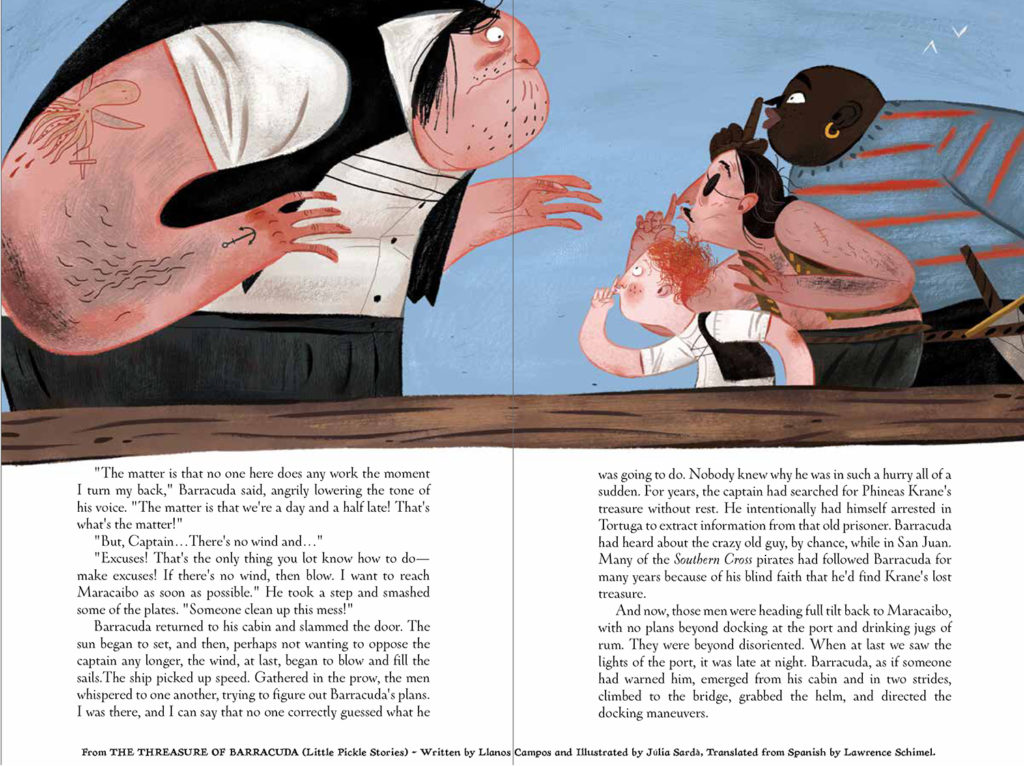

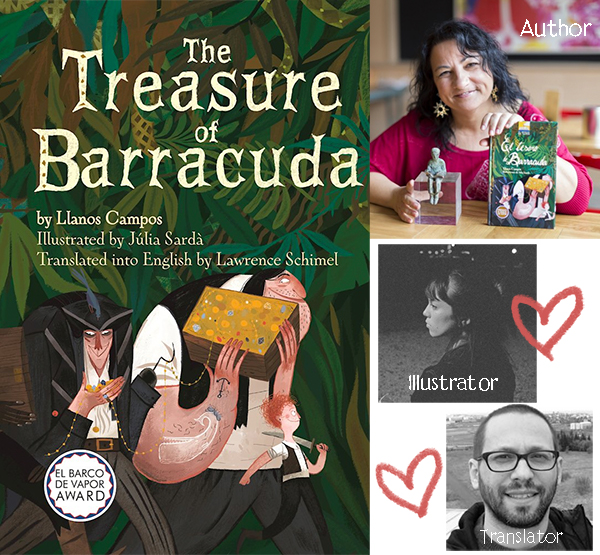

Lawrence Schimel writes in both Spanish and English and has published over 100 books in various languages. In addition to his own writing, Lawrence translates books from Spanish into English, and one of his most recent translations was middle grade novel The Treasure Of Barracuda, written by Llanos Campos and illustrated by Júlia Sardà, recently published by Little Pickle Stories.

You can find more info about Lawrence Schimel at A Midsummer Night’s Press, on Twitter and Facebook.

Lawrence was kind enough to answer some questions about himself and translating books:

Q. How many languages do you speak?

This is an interesting questions. I only create in two languages (English and Spanish). However, I’ve actually translated myself and been published in two other languages (Galician and German). But I’m not able to create in either Galician or German, even though I’ve translated myself into them.

Translating, I am most comfortable working between English and Spanish. Although I can work (laboriously, with a dictionary) from a few other related languages as well (Portuguese, Italian, etc.) but usually only do so for poetry or children’s books, and preferably where I have contact with the authors directly to be able to go over questions, doubts, or issues that arise. When I was in school, I studied Latin and Greek and Old Norse–none of which I can actually speak, and which I’ve mostly now forgotten over the years.

I’ve also sometimes translated work into Spanish from other languages, using English as a bridge language, in poetry workshops where we dialogue directly with the poet whose work is being translated. Lately I’ve been working directly with some Latvian writers to translate them into Spanish, since there are no literary translators working in that combinations; one book of poetry for adults and one picture book are both forthcoming in Spanish next year.

Q. How did you become a literary translator?

I started translating by being a writer first, and one who writes in both Spanish and English. Even though English is my mother tongue, curiously enough, some of my own Spanish-language titles have been translated into English by other people, like my picture book LET’S GO SEE PAPÁ illustrated by Alba Marina Rivera, which was translated by Elisa Amado and published by Groundwood.

Translation, especially for poetry and picture books, can often be the closest reading of a text, and those are often the texts that can be hardest to re-create in another language. So I think that publishers often like to have poets or writers themselves as the translators, who have the sensibility to walk along the tightrope of fidelity to the original text and faithfulness to the reader in the target language, and who can take those leaps when necessary. I have recently been working with a Latvian poet to produce Spanish versions of his poems, using an English draft as the bridge language; there have been a number of times when we’ve come up with a poetic solution in Spanish that he likes so much that he goes back and corrects the English version (which were done by a direct Latvian-English translator, although a linguist not a poet).

In Spain, where I live, translators are considered “authors” of their versions, and copyright law acknowledges the authorship involved in producing their translations and protects that.

Q. How did The Treasure of Barracuda get chosen to be translated? Did the publisher approach you? Did you approach the author? etc.

The Treasure of Barracuda won the Barco de Vapor Prize from the Spanish published Ediciones SM. I have worked with SM for some years now, where they commission sample translations of the opening chapters of some of their titles, to help them sell the foreign rights. Sometimes these translations help find publishers in non-English-speaking countries, where the editor might read English but not Spanish.

Little Pickle Stories was able to read the sample, and fell in love with the book and bought the rights in English. And because they liked the sample, they asked me to continue translating the book. (This is not always the case, and that is one of the “tricky” issues involved with publisher samples, from the translator’s point of view. Some publishers have their own “stable” of translators they work with regularly, so just because you’ve done the sample is no guarantee that you’ll be commissioned to complete the book, although that is often the case.)

Now that the English edition has just been published, it’s helping the story find readers in other countries as well. (A Latvian editor who knows me, but who doesn’t read Spanish, decided to read the English translation specifically because I had translated it and contacted me just befre the Frankfurt Book Fair asking for an introduction to the Spanish publisher so they could try and buy the rights.)

Q. How does book translation work, in terms of process?

There are so many different paths to publication in translation. Sometimes an agent or the rights department for a publisher will pitch projects to potential foreign publishers who might be interested. This is what happened in the case of THE TREASURE OF BARRACUDA, which was published by a large publisher that has its own rights department and is active at the international book fairs.

This book was also very visible to foreign publishers because of winning the Barco de Vapor prize–as well as other honors like being chosen for the White Ravens by the International Youth Library in Munich. Any such distinction is useful for foreign publishers, since not only can they use it in their sales/PR material, which helps when launching an author who is unknown in their territory, many publishers also use it as a way of evaluating what titles to pay attention to, especially if they don’t speak the language themselves and need to rely on external readers who they might pay to do a reader’s report, evaluating the title and its possibilities for their market, or if there is a sample translation they can use.

But very often a translator is the staunchest advocate for a book.

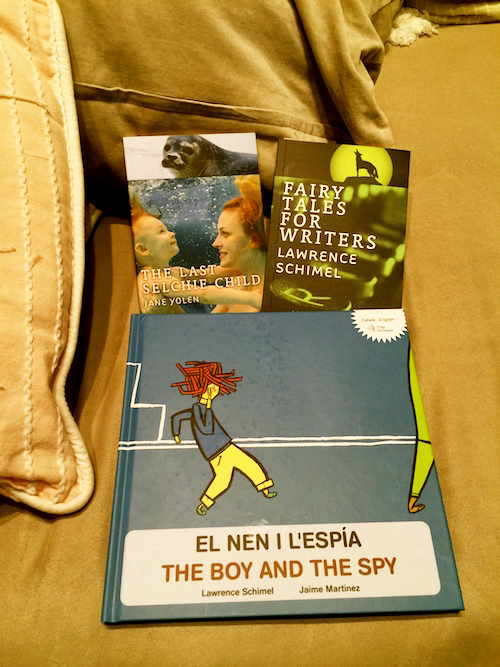

As an example using one of my own books, I took part in a poetry translation workshop a few years ago, where one of the poets involved was the Hungarian poet and translator Anna T. Szabo. Even though we worked on our poetry at the workshop, since we both also write and translate children’s books, I showed her some of my own picture books, she loved one (THE BOY AND THE SPY) and did a translation of it and offered it to one of the publishers she works with regularly, who offered us a contract. (In this case, the artist was someone I know directly and the Spanish publisher of the book had only bought rights in Spanish, Basque, Catalan, and Galician; we still held all other rights ourselves.)

I know that I’ve certainly done the same thing, championing books that I love and want to see published in English (or in Spanish). One year at the Bologna Book Fair, I fell in love with the stories produced by Fatmeh and Zahra Sarmashghi, two sisters who write and illustrate together, and whose books are published by Shabavitz in Iran. I brought the editor of a Guatemalan publisher I work with, Amanuense, to show them the titles, and she fell in love with them, too. I was able to act as interpreter/intermediary to help them negotiate a deal to buy rights to one of the books, and then I translated the text into Spanish, which was published as BALLENA NEGRA.

Sometimes, of course, one is just asked by a publisher to do a translation–especially once one begins to become known as a translator.

But it is also important for the translator to have an affinity with the text, I think–especially in literary translation. I’ve been asked to translate projects that I’ve turned down, usually recommending another translator who is a better match (for instance, I didn’t have the nautical background to do a good job, I felt, on one book project, and recommend a translator who is also a sailing enthusiast and already had the necessary vocabulary–in both Spanish and English–at her hands).

Q. What do you love most about translating a book?

Helping great voices find new readers in another language. While I am a writer and a translator, I am first and foremost a reader, so being able to help books I love find new readers (who couldn’t read the original) is always wonderful to me

Also, I love when there is a problem or a dilemma that I’m able to resolve or come up with a solution for in the target language

I think it’s important to re-create the reading experience in the target language, and sometimes, especially with puns or plays on word, you can’t translate the literal wordplay, but you can compensate by adding something similar in elsewhere. And when it works out, when it maintains the playfulness of the language even if all the literal jokes aren’t translated, that feels really great.

Q. What do you find to be the biggest challenge(s), when translating a book?

It sometimes takes a little while to hit one’s stride with the voice of each new book. I often go much slower at the beginning of each new project, and need to revise more heavily the opening section after having translated the entire book.

I translated into Spanish a book by a friend of mine, the Icelandic author and illustrator Áslaug Jónsdóttir and am trying to help her find a publisher for it in the Spanish-speaking world. The book presented a lot of problems that required work-arounds or other solutions in Spanish, from the very title itself: ÉG VIL FISK! or “I Want Fish!” In Spanish, there are different words for fish that is food (“pescado”) and fish that is still alive (“pez”) so I changed the title to MAR SABE LO QUE QUIERE (or “Mar Knows What She Wants”) to avoid telegraphing the plot of the book, which involves a very young girl, still with a limited vocabulary, asking her parents for fish and getting all sorts of fish-themed things (a toy fish, a dress with fish on it, a fish puzzle, etc.) but being fed everything but fish, which is what she’s asking for. I think the final result works very well, but it took a lot of deliberation to figure out how to make things work out naturally

It is a license to change the girl’s name to “Mar” (which is both a common female name in Spanish but also means “the sea”) but it adds an extra language-specific resonance which I think works well.

I think rhyming texts are also particularly challenging, since normally the same words don’t rhyme in the target language, requiring a transcreation more than just a translation.

Q. What advice do you have for aspiring book translators?

Always, with anyone involved with anything creative, I’d remind them to have fun, that even though it is work and a profession, and it is important to be paid fairly for the work we do, it is also important to keep our love of language and not lose that. So don’t be afraid of working on things, just for yourself, because practice is also the only way to get better as a translator or a writer

The truth is that there is a lot of business involved in being a translator, outside of the actual work of translating. Very often, most editors won’t be able to read in another language, so it usually falls onto the translator’s shoulders to scout for books they want to translate, contact whoever controls the rights to see if they are still available, write a synopsis or sample translation (on spec or not), and on top of everything else, pitch it to publishers until finding one to take it on. And THEN you get to do the fun part, which is the work of translating the book it

It can be very hard to get a foot in the door as a translator, as in most creative professio

Doing reader’s reports for publishers is a badly-paid task that allows one to establish a relationship with an editor, for each side to get to know the other’s taste, etc. It does also show one how and why books get picked (or not) since sometimes something you love (as literature) gets turned down (for commercial reasons) or vice versa.

For children’s books, the SCBWI now has a separate category for translators, and can offer both networking and other support and advice.

Depending on the languages you’re translating from, it may be possible to find work translating samples or extracts from new books, for institutions like NEW BOOKS IN GERMAN or KOREAN LITERATURE NOW, or directly for publishers or literary agents. Many countries or languages also have schemes to help train or support new translators, especially from “smaller” languages.

There are also translators’ associations, like The American Literary Translators Association (ALTA) in the US or the Translators Association in the UK, that offer advice, networking, calls for translators, etc. for members.

Q. What are you excited about or working on now?

I’m working on a great middle grade novel by Mexican writer Juan Villoro called THE WILD BOOK that’s forthcoming in Fall 2017 from Yonder, the new kidzbook imprint from Restless Books. It’s a magical story about libraries and reading, and how sharing books with people you care about can change the reading experienc

Q. What are you reading right now?

I’ve just gotten back from the Guadalajara Book Fair, so I have a bunch of new books I’m eager to dive into. Two are by Mexican author Toño Malpica, whose work I quite admire and who I would love to translate (publishers who might be interested, get in touch with me!). One is POR EL COLOR DEL TRIGO (“By the Color of the Wheat”), a middle grade novel illustrated by Basque artist Iban Barrenetxea and published by Fondo de Cultura, featuring Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (the author of THE LITTLE PRINCE) as the protagonist. The other is MARGOT, a science fiction novel featuring the 8 year old girl of the title, published by Editorial Norma, whose small acts of solidarity and kindness wind up having a far-reaching impact on the fate of humanity.

For more insights from book creators, see my Inkygirl Interview Archives and Advice For Young Writers And Illustrators From Book Creators.