I met Hélène Boudreau through Torkidlit, and have continued to be impressed by this woman’s energy and enthusiasm for kidlit/YA online and offline. I interviewed Hélène a couple of years ago about her book, REAL MERMAIDS DON’T WEAR TOE RINGS, and am delighted to be interviewing her again about her picture book, I DARE YOU NOT TO YAWN.

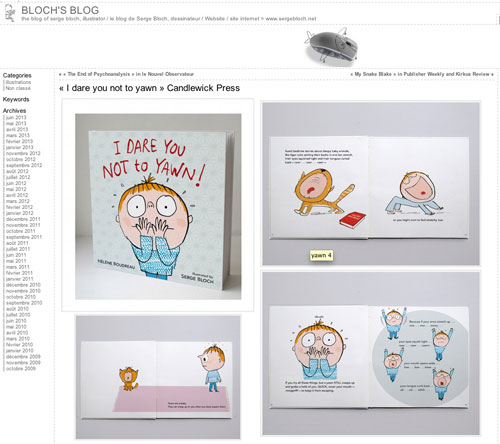

The book just recently came out from Candlewick, and has hugely adorable illustrations by the French artist, Serge Bloch.

Hélène is an Acadian/Métis writer and artist. A native of Isle Madame, Nova Scotia, she writes fiction and non-fiction for children and young adults from her land-locked home in Markham, Ontario, Canada. She has published five non-fiction and nine fiction books for children and young adults, including the picture book I DARE YOU NOT TO YAWN (Candlewick) and the tween series REAL MERMAIDS (Sourcebooks/Jabberwocky).

You can find more info about Hélène at her website, on Twitter, Facebook and Goodreads.

Q. What is your writing process?

People are often surprised when I tell them it took me three times longer to write and revise my 400-word picture book, I Dare You Not to Yawn compared to my 50,000 word novels from my Real Mermaids tween series but it is absolutely true. That said, the process for creating both is quite similar. When I speak to school groups about my writing process, I do it in terms of the ABC’s of writing. Of course, it’s not as simple as that sounds but it’s really all about:

Aha! Getting your brilliant idea and developing it. Begin! Putting pen to paper (or pixel to screen) and giving into your story with wild abandon. Complete! Seeing your story through to the end, being open to criticism, and not giving up until it is as perfect as you can make it.

Aha! I tend to get my ideas in stages. Usually, when something strikes me as a great picture book concept, I jot it down in my ‘Ideas’ folder and let it knock around in my noggin for a few weeks or months. I poke at it with a stick, wondering how to attack it, then finally one day the moment seems right and I start writing things down.

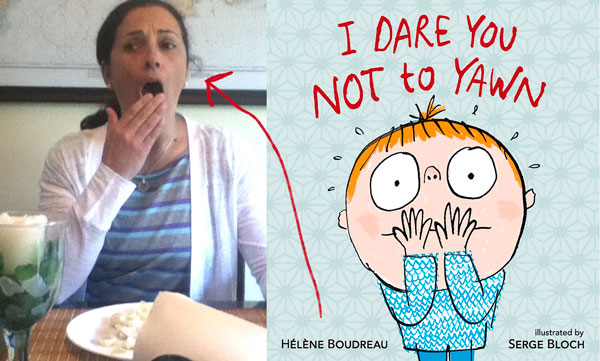

For I Dare You Not to Yawn, the idea originated when my daughter was about 4 years old. She would do this thing at the dinner table where she’d let out a great big yawny-YAWN then watch to see what would happen. Of course, then I started yawning. Then so did her sister and her dad. Soon, we were ALL yawning until we finally figured out she was doing it on purpose!

Of course! Yawns are contagious! Perfect idea for a bedtime story.

So, that was the kernel of the story. I thought about that for a long time, wondering how I would approach the concept and turn it into a picture book. Because of the subversive nature of my daughter’s antics, though, I knew I didn’t want it to be just a sweet, lulling, comfy bedtime story. Instead, I wanted to turn the idea on its ear and approach it from a slightly different angle, which gave me the idea to write an anti-bedtime story (i.e. a how-to guide to avoiding bedtime). Of course, the ultimate outcome remains the same—making kids feel sleepy and cozy and ready for bedtime—but I wanted the child to be an accomplice with the narrator in a way where everyone understands where the story is going but happily tags along for the ride.

Begin! Now was the time for research. First, I made a list of any yawn-inducing images I could think of: bed time stories, lullabies, comfy stuffies and yawning baby animals. But that wasn’t enough. Since this book was meant to be a read-aloud, I actually needed to use words that mimicked the action of yawning. Mouth-stretching words like rawr and baabaa and of course yawn itself. This would make the reader open his/her mouth W-I-D-E to actually induce the reflex to yawn while reading.

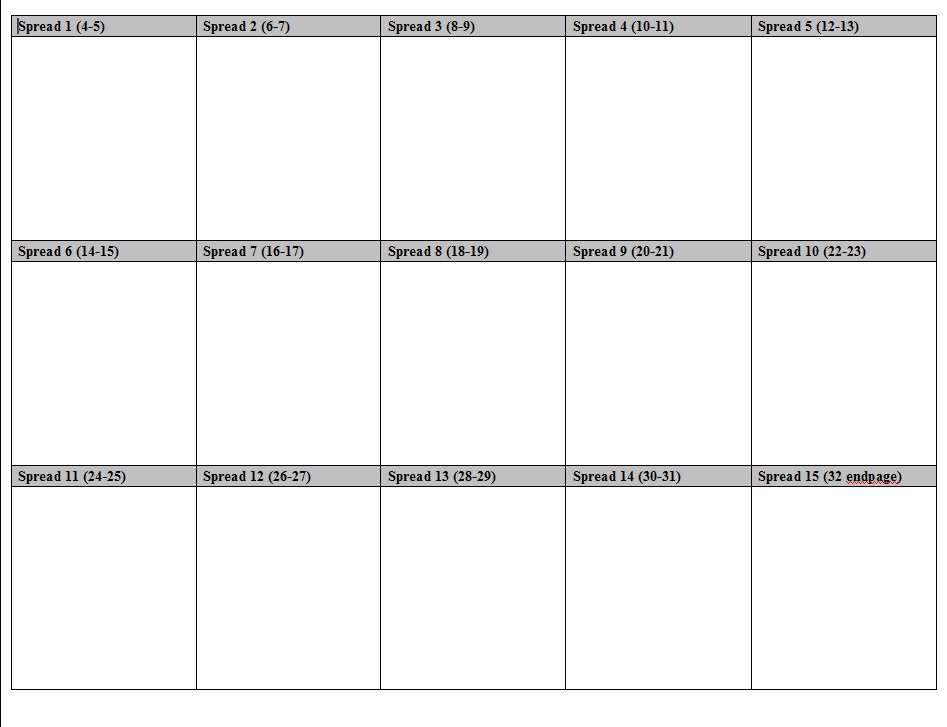

Then, I started writing. Sections of the manuscript came all at once, other parts took more time but the first draft took a period of a few months, I would say. In the initial stages of writing picture books, I organize my writing in a spreads template, which is typically a 5 x 3 table to represent 15 spreads, which is a typical amount in a 32-page picture book.

Breaking text into spreads like this can really help in studying the pacing of a story. I experiment and layout my text in a 5 x 3 grid and also a 3 x 5 grid to see how the story ‘chunks up’ (that’s a technical term *wink*). The story I’m writing at the moment, for example, works best in a 4 x 4 grid and gives the story its best symmetry.

It’s wonderfully useful to start thinking in two-page ‘spreads’ like this when writing picture books because it lends itself well to the illustration end of things. If you take a look at my illustrator’s website for I Dare You Not to Yawn, you’ll see what I mean. I’ll wait here while you do that. But, please come back. I’ll miss you…

Click image above to visit illustrator’s blog post about I DARE YOU NOT TO YAWN

Serge shows a couple of spreads of his illustrations based on the breakdown of my text. In some spreads like (spread 1/ page 4-5) the text only happens on one page, though the art spreads across two. In another, like (spread 2/ page 6-7) the text and pictures are broken up into two distinct entities, and finally in (spread 8/ page 18-19) both the text and the pictures flow over the two pages.

When submitting my manuscript to my editor, though, I don’t use the table since it makes it hard for her to make editorial comments. I format my text like a typical manuscript and label each spread with headings so she can visualize the page breaks. Example:

Spread 1 (page 4-5)

Text, text, text…

Spread 2 (page 5-6)

Text, text, text…

and so on until

Spread 15 (page 32)

Text, text, text…

I keep my ‘illustration notes’ as sidebar ‘comments’ or numbered footnotes so they don’t clutter the text.

IMPORTANT: be mindful to only add illustration notes when absolutely necessary (ie when the text has a double meaning, which is not obvious, frex).

Complete! Now that I’ve worked on my text and have revised it within an inch of its life, it’s the time to show my work to a few trusted critique friends, my kids, my husband, my agent and whomever else will be gracious enough to read my story. This is the time I’m most possessive of my words—like showing off your newborn baby to the world and daring anyone to tell you it’s not the most beautiful creature they’ve ever seen. But, of course, I need to get over myself and allow the story to be vulnerable for a while. This is the final step before I send my story to my editor so I want it to be the best I can make it. Do I pout? Lots! But it’s for the greater good and I work on my story for a few more months in this manner.

Finally, it’s time to share my manuscript with my editor. By now, I Dare You Not to Yawn had taken about a year and a half to write and revise in its various iterations. I had shared it with at least a dozen people so I had a lot of opportunity for feedback. You would think, at this point, that the story was pretty much ready to send to the printing press, right?

Not so fast, cowgirl.

Before acquiring the project, my editor and I did a pretty intense round of revisions. I worked for weeks to get it perfect then sent it off again, hoping I’d struck the right chord. I must have done something right(ish) because a few days later my agent called with the news that Candlewick would, indeed, like to publish I Dare You Not to Yawn. That was in Fall 2009.

*cue 76 trombones in a big parade*

Can I haz a picture book published now, plz?

Nuh-uh, hold your horses sum’more!

It actually took 18 more months and 6 major revisions for my editor and I to get the text in shape enough so that Serge Bloch could get started on illustrations. Bless my editor’s heart—she was SO patient with me as we worked on draft after draft (after draft). There were times when I honestly thought I should give back my advance money and call it a draw. But I tried to put my trust in the editorial process and we persisted until I heard the precious words; “It’s ready!”.

And as a special treat (or possibly an exercise to discourage anyone from attempting to publish a picture book, like EVER), my editor has given me permission to share the evolution of that text with you here. The following is the step-by-step process (with some, but not all, of the line edit comments and her general editorial comments as footnotes) of how the text changed over that period of a year and a half. There were still a few tweaks after this once we had the context of Serge’s illustrations but you get the picture.

PDF: Evolution of I DARE YOU NOT TO YAWN over six drafts (124k)

In total, from editorial acquisition in fall of 2009 to revisions and illustration to publication in spring of 2013, it was nearly a four year process.

Was it worth it? Totally!

But, hopefully, now you can understand why it took me longer to write, revise, and publish this 400-word picture book compared to my 50,000 word Real Mermaids novels. *wink*

Q. What advice do you have for aspiring picture book writers?

No matter how good you think your idea is—the next one could be better.

It is so important to be constantly generating ideas as a picture book author because, for example, of the thirty or so picture book manuscripts I have in various stages of development on my hard drive, only two (so far) have been actually published. Those are not great odds but the more you create the better chance you have of success. I often see authors fall in love with ONE idea and work and work and work on that idea at the expense of creating new stories. I admire their tenacity but it might not be the best approach at hitting on not only a good idea but a marketable idea. I try to think of those other 28 ideas on my hard drives as prototypes. Good but not GREAT. Keep it fresh and keep it moving, people!

No matter how good you think your book is—it can be better.

There are so many things authors can do to raise their game. My writing improved by leaps and bounds when I joined a critique group. Revision, revision, revision! It’s the process of sculpting away the excess clay to reveal your masterpiece inside. In my case, though, I can only take my story to a certain point on my own (maybe the ‘good’ point?) but need objective feedback to help take things from ‘good’ to ‘great’. Reading many, many, many books in the picture book genre to get a sense of how the pros do it and reading books on ‘craft’ can be useful as well. Going to conferences, reading articles and joining professional author associations are a wealth of information as well.

It’s not one thing, it’s everything.

No matter how unfair and just-plain-wrong the comments from your critique partner/agent/ editor seem to be—there is usually truth in every critique. It’s your job to pull out the ‘why’ of their reactions.

This can be so frustrating. Just recently, my agent critiqued a picture book manuscript of mine and while she loved the overall concept she thought my ‘punch line’ in spread #13 could use more punch and she gave me a potential example of how I could spice things up. “Are you kidding me?” was my first response, “my idea is MUCH more brilliant! Why can’t she see that??”. (LOL, sorry super agent, Lauren…)

So, I sulked for a while (three weeks, to be exact), asked two other people for their advice in the meantime (one who agreed with her, which made me sulk even more) then got over myself and tried to look at my agent’s comments in a less egotistical/prima donna manner. Now, finally, I am realizing that even though my agent had given me an example of how the story could be better, that was merely a jumping off point for me to push myself and get the story to the next level.

Was she right after all? Begrudgingly, yes. There is a problem with the punch line. My agent was merely pointing that out. Now, it’s my job to figure out how to fix it.

Q. What are you working on now? Any other upcoming events or other info you’d like to share?

At this very moment, I’m working on revisions for the fourth book in the Real Mermaids series. I’m also working on a new picture book, which I hope will be a companion picture book to I Dare You Not to Yawn but that remains to be seen—if only I can sort out spread #13!

You can connect with Hélène at her website, on Twitter, Facebook and Goodreads.

TWEETABLE:

Author @HeleneBoudreau shares revision/editorial notes for 6 drafts of pb I DARE YOU NOT TO YAWN: http://bit.ly/yawnbook (Tweet this)

Revision process = sculpting away excess clay to reveal masterpiece within. @HeleneBoudreau tips: http://bit.ly/16buCyn (Tweet this)

———————————

For more insights from book creators, see my Inkygirl Interview Archives and Advice For Young Writers And Illustrators From Book Creators.nterview Archive.